In the absence of anything better, the jamun makes a decent pie”. On the other hand, “the guava makes a good jelly”. Written with a pencil in cursive, the verdicts on homegrown fruit don’t belong to a farm-to-table meal kit but to a 150-year-old book titled ‘Flowers of Bombay Presidency‘.

Featuring 202 watercolour paintings of flora ranging from marigold to mango, the giant publication from 19th century Bombay began as the pastime of one Mary Elizabeth Butt who sketched the flowers and fruit she chanced upon in gardens spanning Matheran to Mahabaleshwar and added notes on their local names, habitats, scent, taste and nutritional use. As a tribute, her husband, William Butt, later completed her sketches, creating the rare 1884 book that ended up helping researchers of Western and Ayurvedic medicine.

Starting March 29, ‘Flowers of Bombay Presidency’ will sit alongside folios from a 17th-century treatise on medicinal plants of Kerala called Hortus Malabaricus and a 120-piece mosaic of botanical observations by miniaturist Gopa Trivedi as part of a month-long exhibition at Sarmaya, a “museum without boundaries” in Fort which–much like William Butt’s book–started life as a husband’s tribute to a wife.

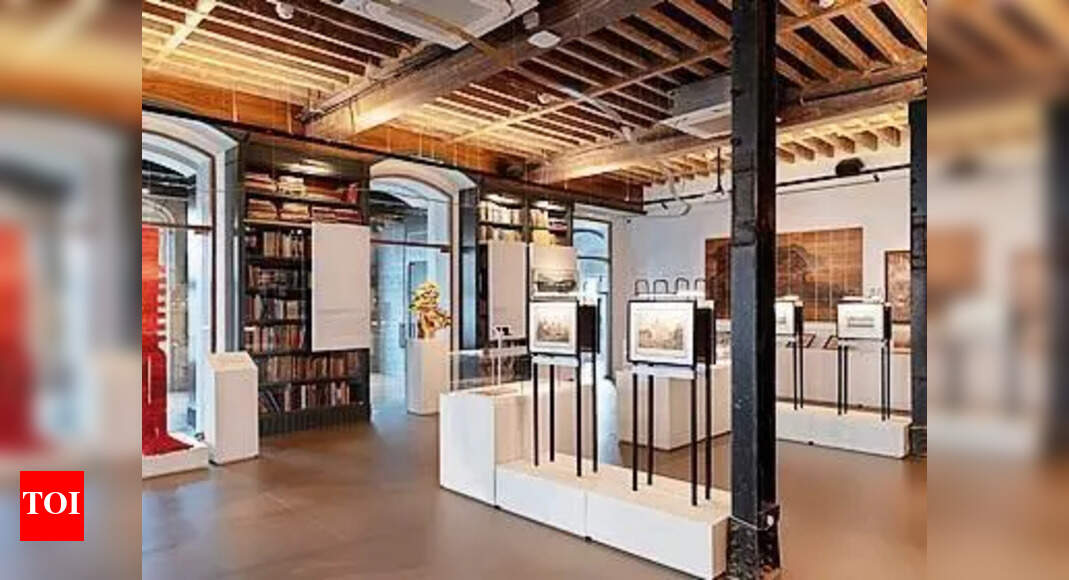

Launched last year by former banker Paul Abraham, the sprawling 3,500-sq ft Sarmaya is the culmination of a decade-old digital archive cum physical setup in Dadar through which Abraham honoured the memory of his wife and fellow art collector, Tina, who died of cancer in 2014. Housed in the iconic 146-year-old Lawrence and Mayo House on D N Road, it surprises first-timers. “Is it a gallery, an archive or a museum?” people wonder on stepping into the roomy, book-lined building, which once housed a bank and whose vault now boasts silver and gold coins ranging from 6th-century Delhi to 20th-century Kerala.

Abraham was a teenager in Delhi when his father, a Malayali who grew up in Kerala, gifted him a bottle of rare coins from Travancore. With their royal insignia and intricate engravings, the coins not only connected Abraham to his roots but to a broader historical narrative, kickstarting a half-century-long fixation with vintage engravings, maps, photos and artefacts.

While love for coins led him to Mughal-era sites such as Najafgarh and Tughlaqabad, Tina’s passion for indigenous art introduced him to Gond paintings and Tholu Bommalata (leather puppetry). In her memory, Abraham launched the private collection as an archive in 2015 that could also be accessed digitally. Later, he would meet Pavitra Rajaram, now his wife and co-founder of Sarmaya, whose passion for design and art history is reflected not only in the many women artists featured in the collection but also in touches such as the metallic outline of South India that runs across the ceiling.

From a letter written by Prince Ghulam Muhammad Sultan, 14th son of Tipu Sultan, to Captain Peacock, a British govt official, to silver medals that offer a peek into the Khedda system (by which wild elephants were captured to be domesticated till the practice was banned), Sarmaya’s collection can be accessed through the museum website. “Purists may look down on it but digital is not a lesser way of engagement,” says Abraham, explaining why their Youtube channel and social media page drives up interaction.

Sarmaya’s inaugural exhibition was in Jan this year. The Dappled Light’, an upcoming showcase of India’s natural history, is aimed at connecting with young minds through its curation of forest-inspired fragrances, tree walks, screenings and workshops (March 29 to May 4). Amritha Nair, research associate at Sarmaya, puts on a pair of blue plastic gloves and pulls out a freshly-imported 1838 book full of hand-painted birds from a drawer. Placing it on a slanting reading shelf, she opens to a page and points to bottom left. ‘Vishnupersaud,’ it says here in cursive. “This was probably the first time an Indian artist was acknowledged by name,” says Nair. “It’s only when we truly see and appreciate our natural heritage that we feel compelled to protect it,” says Abraham.